Famine menaces 20m people in Africa and Yemen: The Economist

OUTSIDE a thatched hut in Panyijiar, in South Sudan, Nyakor Matoap, a 25-year-old woman, clutches the youngest of her three children. Dressed in a silky emerald shawl, she hides the baby, named Nyathol, underneath its folds. Her other children crowd happily enough around her legs. But the baby is in a bad way. Though almost a year old, he is scarcely larger than a newborn. When he cries, it is quiet and gasping, his tiny ribs pushing out his chest. His swollen head lolls uncomfortably on his emaciated frame. Asked whether he will survive, she replies simply, “I do not know.”

Before 2013 Mrs Matoap cultivated a patch of land near Leer, some 80km (50 miles) further north. But then civil war broke out in South Sudan, and her husband went to join rebel fighters. In August last year, government forces came into her village. They pulled the men out of their huts and shot them; the women fled. She found herself in the murky waters of the Sudd, a vast swamp which spreads either side of the White Nile. For seven months she has lived off wild fruit and the roots of water lilies. She last saw her husband in 2015, when her son was conceived. Though Panyijiar is friendly territory, and home to an aid camp run by the International Rescue Committee, she does not believe her ordeal is over. “I thought the war would never reach us in Leer,” she says, “so I cannot say that it won’t come here.”

In February Leer was one of two counties in South Sudan declared to be in a state of famine by the UN. Between them they are home to 100,000 people. It is the first time since 2011 that the term has been used and only the second since the organisation adopted the IPC scale, a scientific way of determining levels of food insecurity. Another 1.1m people live in areas in an “emergency” situation, one step short of famine, but where people are still dying from lack of food. Across South Sudan as a whole, the UN judges that some 250,000 children under the age of five suffer from “severe acute” malnutrition, meaning that if they do not receive treatment they will probably die. Some 5.8m people will rely on food aid this year.

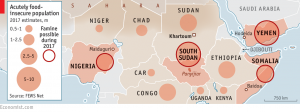

South Sudan is not alone. According to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS Net), run by the American government, 70m people around the world will need food assistance this year, a level it says is “unprecedented in recent decades”. Three other countries, Nigeria, Somalia and Yemen, have what it calls a “credible risk of famine”. Between the four, 20m people risk starvation. Like extreme poverty, famine has been driven from most of the world (see article). But in those countries it is burrowing in.

Aid agencies are frantically fundraising; the UN says that another $4.4bn is needed by July. Yet a shortage of funds is hardly the only problem. What Somalia, South Sudan, northern Nigeria and Yemen have in common is that they are all at war. These days famine is never just a natural disaster; it is always a product of politics.

In South Sudan food insecurity has been growing since December 2013, when civil war broke out between different factions of the SPLA, a rebel group that won independence from Sudan in 2011. Since then the war has spread and the country has split along ethnic lines. The government, much like the previous Sudanese government in Khartoum, tends to fight by targeting “enemy” civilians. Since 2013 over 3m South Sudanese (out of a total of 11m) have fled their homes to escape ethnic killing. People who have fled cannot harvest their crops or work to pay for food. Like Mrs Matoap, many are forced to live off what they can find in the bush while they try to get to somewhere safer.

Acts of man, not God

The government deserves much of the blame. It has little interest in helping aid get in and indeed often seems determined to stop the flow. The UN reports 967 denials of humanitarian aid that affected children from the outbreak of war to December 2016—there were almost certainly more. One UN official explains how the government uses regulations to stop food deliveries: “You get the 17 forms you need and suddenly they invent another.” A second official notes that, on several occasions, convoys have been stopped by SPLA soldiers who accuse the drivers of feeding the enemy. Few aid workers think the government actually wants people to starve. But they reckon it would rather let children die than risk supplies getting into the hands of enemy soldiers, who could sell them to buy weapons.

South Sudan is not unusual in having a man-made famine. In Yemen the political dynamics are different but the result is the same. According to FEWS Net, 2m people there are in an “emergency” situation. Another 5m-8m do not have enough to eat. The main reason is that the coalition led by Saudi Arabia, which is fighting Houthi rebels in the north-west of the country, does not allow food through its maritime blockade without a lengthy permit process, by which time much of it spoils. Nine-tenths of Yemen’s food is imported, but Hodeida, the largest port, has been bombed out. At a warehouse in Humanitarian City, a storage centre used by aid agencies in Dubai, four new mobile cranes are waiting to help Hodeida unload ships. When the UN tried to install them in January, the coalition denied them permission to enter Yemeni waters. They might be used for offloading weapons, an official explained, or to earn port fees for the rebels. That is despite the fact that ships docking at Hodeida are inspected by the UN, and arms anyway enter elsewhere, on small boats or overland.

South Sudan’s and Yemen’s are the most clearly avoidable famines. But Nigeria’s comes close. There, a famine may already have happened late last year—nobody is sure, because it was too difficult to gather data. Over the past two years, as the Nigerian army has clawed back towns in the north-east of the country from Boko Haram, an Islamist group, starving people have poured in from nearby villages. The population of Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, has doubled as almost 800,000 hungry displaced people have moved into makeshift shelters there. Perhaps as many remain in areas that aid workers cannot reach. Part of the reason is that the Nigerian army does not allow them in. But most aid agencies are reluctant to deliver food in areas held by murderous jihadists anyway. “You don’t really have someone to negotiate access with,” says Peter Lundberg, the UN’s deputy humanitarian co-ordinator in Nigeria. Still, in the areas that the army has secured, malnutrition has fallen sharply.

Only in Somalia, which in 2011 was the last country to suffer an officially declared famine, does the risk of starvation derive in large part from weather. A drought afflicting much of east Africa has wrecked crops and killed animals. “I am 73, but I have a very sound memory and what I am saying is true: this is the worst,” says Mohamed Yahir, a farmer in the south-western city of Baidoa, whose past three harvests have failed and whose livestock has all died.

This year’s Somali famine may be easier to tackle than the one in 2011, when al-Shabab, a vicious Islamist militia, held a much larger part of the country. Now, aid is at least trickling in. But a hangover from the former troubles remains. Without much of a state, and men with guns everywhere, much of the Somali hinterland is still too dangerous and expensive for aid to get to where it is needed.

A challenge to the world

What does the return of famine mean for international organisations such as the UN and for Western countries, which provide most of the finance for emergency aid? The UN’s humanitarian co-ordinator, Stephen O’Brien, has said that this year is “the largest humanitarian crisis” since 1945. Not so: China’s famine during the Great Leap Forward of 1958-62 caused between 20m and 55m deaths. The situations in Yemen and South Sudan are not yet as shocking as the Ethiopian famine of 1984, when hundreds of thousands of people starved even as the country’s military regime taxed aid and spent the proceeds on a grand celebration of the success of Marxism.

Still, today’s famines are real and severe. Sadly, in all four countries, the global response has been inadequate. Western governments and aid agencies have invested large amounts of money and energy in providing assistance, but they have done little to address the political problems that cause starvation. In South Sudan and Yemen they acquiesce to the obstacles that governments place on distributing aid.

Though there are 17,000 peacekeepers in South Sudan, with a Chapter 7 mandate (which authorises the use of force to protect civilians), the UN is loth to criticise the government that hosts its mission. Yet the government is responsible for most of the violence, and the consequent displacement and starvation. “They want these people dead,” notes a UN official who would never say so publicly. In December the head of the Norwegian Refugee Council was expelled. Both the UN and other Western governments seem to have decided that it is better to shut up than to be kicked out and lose access to the people they are trying to help.

The situation in Yemen is more squalid. There, the weapons used to bomb Houthi rebels are mostly supplied by Britain and America; America has given logistics and intelligence support to Saudi Arabia’s war effort for two years. Yet diplomats tiptoe round criticism of the Saudi-led coalition. They insist that they are pushing for more aid to be allowed in, but shy away from sanctions that might force leaders to comply. One UN official describes a “conspiracy of silence” about Yemen.

That is partly true of Nigeria, too. The release of some of the girls kidnapped by Boko Haram shows that it is possible to negotiate with the jihadists. Yet there is “no conversation” about aid crossing front lines, according to one aid worker. The Nigerian government’s rules about where aid agencies can go are simply accepted, even though starvation has been a weapon of choice for defeating insurgencies in Nigeria since the war over Biafran secession in the 1960s.

According to Alex de Waal of Tufts University, formally declaring a famine is a “political act” that is intended to produce action. “This will be a test case for whether it works,” he writes. In 2011, when Somalia was last hit by drought, the declaration of famine forced America to change the rules that were stopping aid agencies from supplying food to territory held by al-Shabab.

Yet few want to intervene. In 1992 George Bush senior sent American troops to Somalia to force the local warlords to let aid in. Bill Clinton pulled the troops out after some of them were killed, and since then military intervention to end famine has gone out of fashion. In South Sudan, a country created by American political pressure, even introducing an arms embargo or sanctions against president Salva Kiir has proved impossible. Similarly, Britain and America show no sign of wanting to force Saudi Arabia or its allies to curtail their war in Yemen. But there is no alternative plan, either. And so famine, which should have been abolished throughout the world by now, is coming back.